I recently received an e-mail with a question that I have heard many times before. My correspondent questioned why some web sites charge money to access genealogy information. The question was simple: "Why can’t all genealogy information be made available on the web free of charge?"

Indeed, in the U.S. and Canada, governmental records are public domain, available free of charge to those who can travel to the repositories where the original records are stored. Many private records, such as church records, may not be public domain, but they are also often available at no charge if one can travel to view them. When travel is not an option, a trip to a local library may suffice if that library has microfilms of the original records that patrons can view for free. (For this article, I will ignore the costs of sending a filming crew to a repository to make the microfilms and the expenses of reproducing and distributing microfilms. However, those expenses are not trivial.)

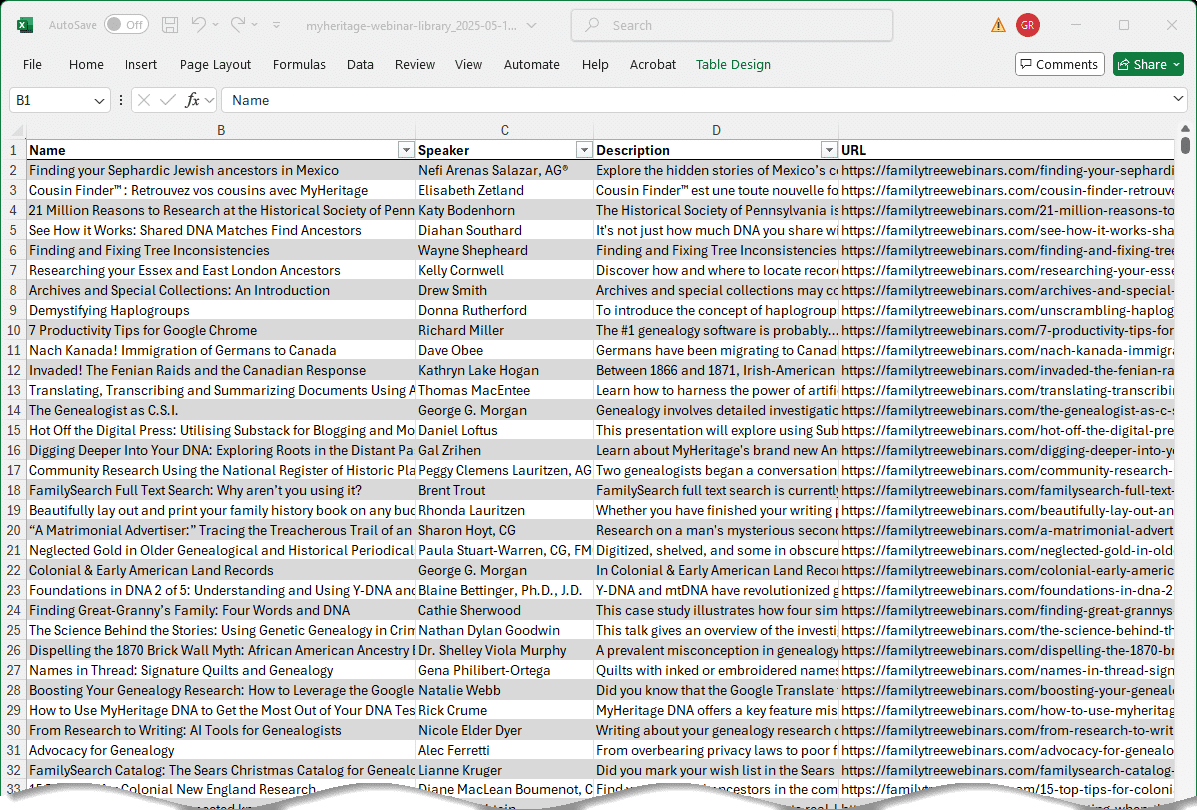

Given the fact that the records are already available "free of charge," one might question the need to pay $50 or $100 or more per year to access the same records on a subscription service, such as Footnote.com, Ancestry.com, Origins.net, NewEnglandAncestors.org, and other genealogy web sites.

First of all, the idea that the records are available "free" is only true for those who live near the repository that houses the original records or photocopies of the records. If you have to travel some distance to a library that houses the records you seek, you will incur travel expenses. Even a trip to a library a few miles away will incur costs for gasoline and perhaps for parking. Such records are not truly "free." A longer trip will incur airfare or automobile expenses, along with hotel rooms and meals. A three-day trip to a distant repository can easily cost $500 or more. For many who do not live near major genealogy libraries, this quickly changes the concept of "free."

From the genealogist’s viewpoint, accessing records published on the Internet greatly increases convenience and reduces travel expenses. However, from the publisher’s viewpoint, the financial realities of publishing on the web add up rather quickly when one looks at the expenses involved with acquiring, digitizing, and electronically publishing records of interest to genealogists. Such an effort is not cheap.

To be sure, there are hundreds of web pages available today at no charge that contain transcribed records from a variety of sources. RootsWeb has many such pages, as do freebmd.org.uk, genuki.org.uk, and many others. These web sites contain records transcribed by volunteers, and someone pays for the web servers without passing those expenses on to users. In most cases, the expenses are not huge, and advertising can help pay the bills. A few of these web sites may even contain images of the original records. Most of these sites have databases that contain hundreds or even thousands of records. In contrast, commercial services typically provide millions of records, usually many millions. With larger databases come larger expenses.

Let’s assume that a company or even a genealogy society decides to make state vital records available on the World Wide Web. Once an agreement has been negotiated with the state, the company or society starts work. I will make some rough estimates of the expenses involved.

In our example, let’s say that the project entails 25 million records over a 50-year period. (This would be for a state with a rather small population; many states will have more records than that in a 50-year period.) Digitizing these records will require thousands of manhours. It is doubtful if anyone can find that number of unpaid volunteers to travel to the repository, run the scanners, and do data entry work. In fact, the repository may not even have room for a crew of that sort.

If you own a scanner, calculate how many pages you can scan in one hour. Then calculate how long it would take you to scan twenty-five million pages. If I can scan a page every 2 minutes for a standard work week, I will need 20,833 weeks for this project. Clearly, hobbyist-grade scanners will never get the job done. Expensive, high-speed scanners need to be purchased. Five thousand dollars is a typical price for high-volume scanners, and this project will probably require two or more of them. Next, operators need to be hired to sit at the scanners 40 hours a week and create the digitized images.

This process only makes scanned images of the records, probably the simplest and least-expensive part of the project. Somebody needs to make indexes as well. The process will vary, depending upon what is already available. In many cases, someone sitting at a computer will need to index each and every one of the millions of entries. Add in many more thousands of dollars in labor charges.

Now we have created images, plus indexes to those images. We need some skilled programmers to combine all the data into one huge database. Skilled database administrators’ labor also is not cheap.

Once the records have been digitized and a database has been created, the real expenses begin. This database with twenty-five million high-quality images requires several terabytes of disk storage. (A terabyte equals one thousand gigabytes, the same as one million megabytes.) The purchase of a high-uptime, high-throughput disk array of that size, along with built-in backup capabilities, easily costs $25,000 or more per terabyte. Add in the expense of a web server, a database, and the required software, and the cost soon exceeds $100,000 for the required hardware and software to make these records available online to genealogists. This figure does not include the labor charges mentioned earlier.

Next, we need very high-speed connections to connect the hardware to the Internet so that we can serve 100 or more simultaneous users who wish to view these large graphics files. A single T-1 line is the minimum requirement for 20 or 30 simultaneous users, but most commercial web servers today are connected by multiple OC-3 connections. (I’ll skip the technical discussion of T-1 and OC-3 connections. Let’s just say that they are very high-speed lines, capable of handling many simultaneous users. They also cost a lot of money.)

In most cases, it is cheaper to install the disk array, database server, and web server at a commercial web hosting service than to build one’s own data center. Hosting fees for a high-usage database start at $1,000 a month and quickly go up. Commercial genealogy companies with lots of users typically pay $10,000 or more per month in hosting fees. This may seem high, but it is still less expensive than building your own data center.

The bottom line is simple to anyone with a calculator: more than a quarter million dollars is easily expended to make high-quality original source records available to genealogists. Following that cost are monthly fees to keep this data available.

The result is a database in which one can search for a name, find it, double-click on the entry, and then see an image of the original record. In other words, primary source records are visible to anyone in Virginia or California or anywhere else in the world with no travel expenses required.

Of course, I have ignored many other expenses. When a popular database of this sort is placed online, users will have questions. Someone needs to answer those questions; so, we must create a customer service department. In the case of a society, a few members might step forward to answer questions. In the case of Ancestry.com, it means several hundred employees and a large building with telephones, computers, and high-speed data connections. Again, you can guess at the expenses.

Where did this money come from?

Yes, it would be nice to provide genealogy information online at no cost. However, if you are the person who wishes to provide that information, a few minutes with a calculator will quickly bring you back to reality.

In fact, the only practical method of placing large amounts of genealogy information on the web is to have someone pay the expenses of acquiring, digitizing, and providing the data. In most cases, this means that the people who benefit will pay. The same free enterprise system allows those with a vision to offer desirable information, gives them the opportunity to earn their living by charging those who take advantage of their efforts, and makes it possible for us all to reap the rewards at a tiny fraction of the provider’s cost.

Just a reminder to everyone that has issues with Ancestry (or other sites). While we as genealogists are commonly willing to share information at no cost with others, Ancestry is not a genealogist. It is a company – specifically designed to make as much profit as possible. If you feel it is too expensive, then do not use it.

I think we should all take a second and remember that what we are really paying for is primarily our own convenience. Less than twenty years ago, in those pre-Internet days, a genealogist would have to write letters or go on day trips to the National Archives or other libraries, etc. around the country – often spending a relative fortune on postage – only to have 8 out of 10 letters come back as dead ends.

We are only paying for the actual information on a secondary level, as the information is available much cheaper the “hard” way.

Remember, of “fast”, “cheap”, and “easy”, we can only have 2 – not all 3!